Political Polls and the Implications of Nonresponse Bias

Election season is upon us and the polls abound. The Columbus Dispatch recently conducted a poll of registered Ohio voters that found Democratic incumbent governor Ted Strickland trailing Republican John Kasich by a whopping 12 points (49% Kasich, 37% Strickland, 10% undecided). In an election season infused with anti-incumbent fervor, Kasich’s lead may not be surprising. On the other hand, this particular 12-point gap seemed a bit odd, and led us to further examine how the poll was conducted.

The Dispatch conducted a mail survey, and calculated poll numbers from the 1,622 registered Ohio voters who completed and returned their ballots. The response rate was 14%, not unusually low for mail surveys. Nevertheless, one might wonder about possible nonresponse bias: did the opinions of the 86% of registered voters who received the ballot but did not return it differ from those who did return ballots? And if so, how might this affect the overall results?

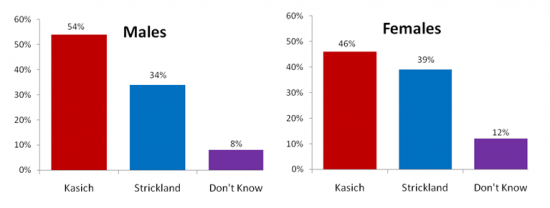

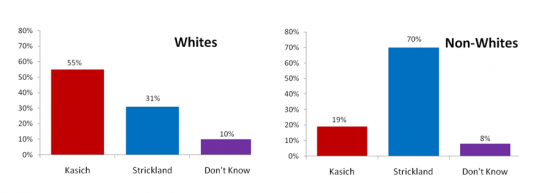

As an example, in the 2006 midterm elections, 49% of actual voters were male and 79% were white. In the Dispatch poll, these groups were overrepresented: 52% of respondents were male and 87% were white. Do these discrepancies matter when drawing conclusions about likely election results? Only if the opinions of male voters differ from female voters, or, if the opinions of white voters differ from the views of non-white voters.

As it turns out, male and white voters are generally more likely to vote Republican than their female and non-white counterparts, as the Dispatch poll itself reveals (see below):

So, would the conclusions drawn from this poll change if more female and non-white voters had returned their ballots? It is likely John Kasich would still be ahead of Strickland, but his lead might not seem so formidable.